https://ift.tt/3xWL774 How To Update Your Beliefs Based On Evidence Do You Have Covid-19? Imagine you took a rapid at-home covid-19 test....

How To Update Your Beliefs Based On Evidence

Do You Have Covid-19?

Imagine you took a rapid at-home covid-19 test. If you test positive, how worried should you be? Alternatively, if you test negative, how safe should you feel?

This article will arm you with the knowledge and the tools to correctly and easily evaluate such evidence and update your confidence in your beliefs/knowledge/hypotheses) accordingly. After all, your life may depend on it.

How Should You Evaluate The Evidence?

Hypothesis

To evaluate the evidence, you first have to take a step back and be clear about what exactly the evidence is for. There is a hypothesis (or a belief if you will) that has some likelihood of being true. In this case the hypothesis is: “You have covid-19”. And the new evidence for that hypothesis is: “You tested positive” (using a particular rapid at-home test).

Prior Likelihood

Before you consider any new evidence for the hypothesis, you estimate the prior likelihood of the hypothesis being true (“prior” as in prior to the evidence). It’s easy enough to find the current rate of new cases in your area. For example, in my county (King County, Washington) there have been 64 new cases of covid-19 per 100,000 residents in the 7 days prior to December 2, 2021. If you live in my area, are asymptomatic, have no reason to suspect recent exposure, and have no pre-existing conditions that make you more susceptible, you reasonably choose the base rate of 64 / 100,000 * 100 or 0.064% as your prior likelihood of having covid-19 now.

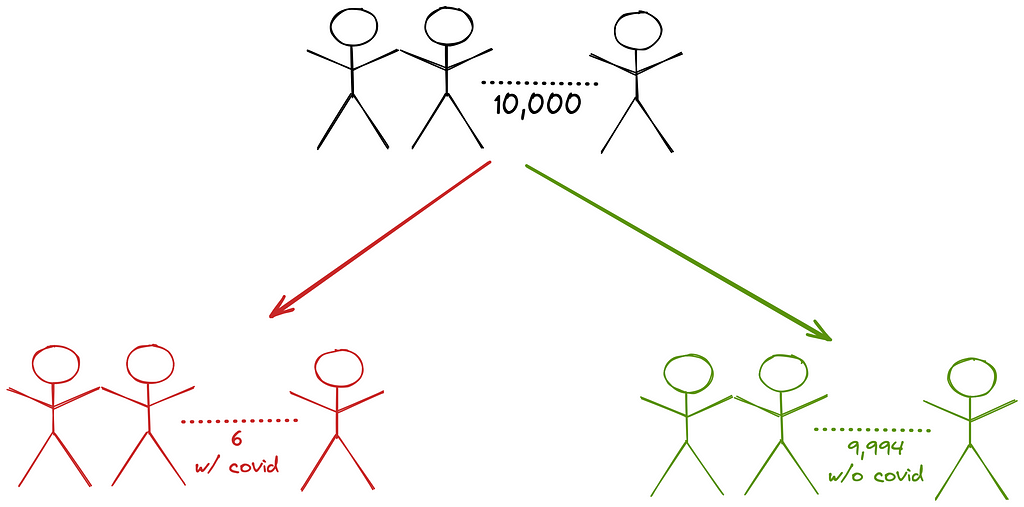

This prior likelihood indicates that out of a sample of 10,000 people, about 6 have covid-19 and 9,994 don’t.

Posterior Likelihood

Then you consider the new evidence (you tested positive) for the hypothesis (you have covid-19). You update the prior likelihood (0.064%), based on the new evidence, to get the posterior likelihood of the hypothesis being true (“posterior” as in after knowing the evidence).

This requires two pieces of information.

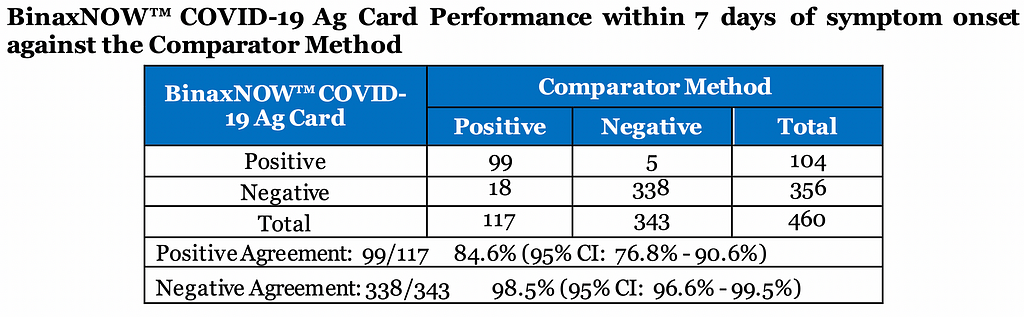

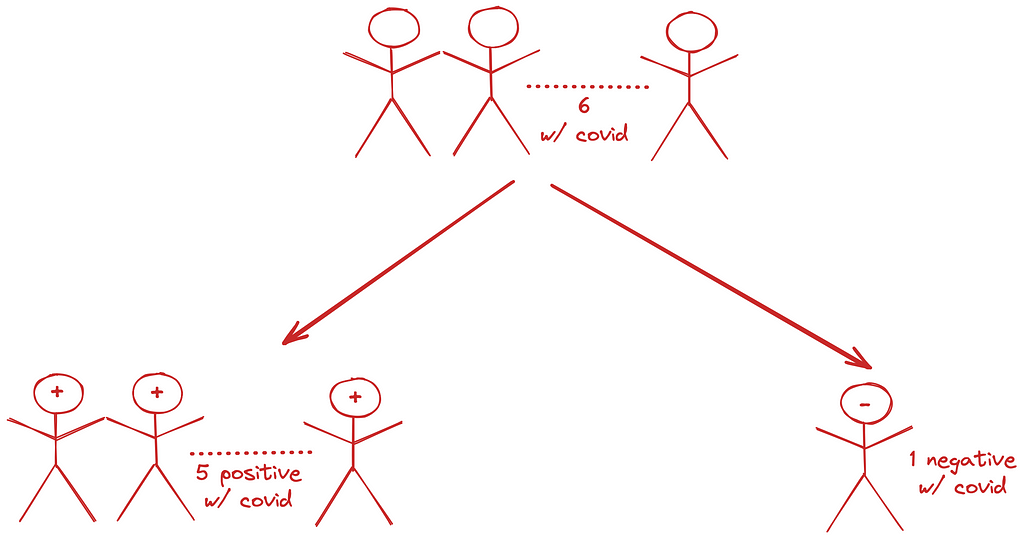

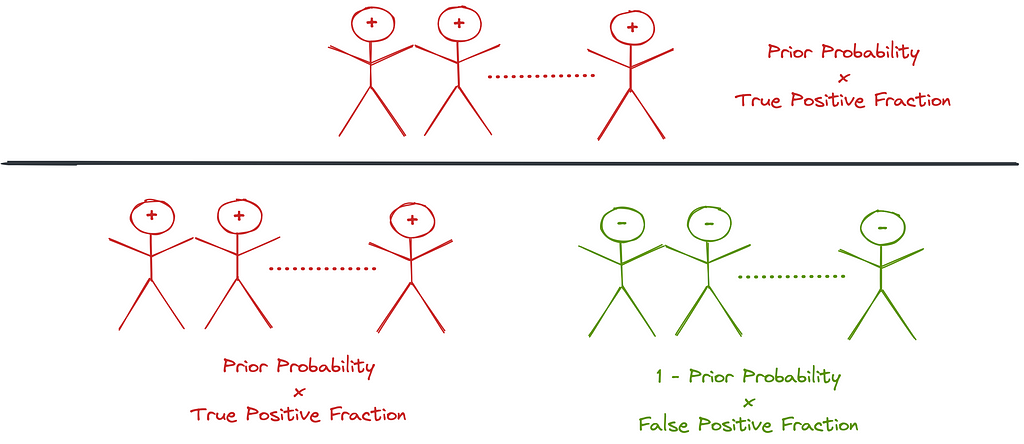

- What is the likelihood of the evidence, if the hypothesis is true? In this case, how likely is it that you test positive if you indeed have covid-19? This is the true positive rate. From the data for one commonly used rapid test (BinaxNow), the true positive rate is 84.6%. This means that out of every 1,000 people who have covid-19 and take the test, about 846 test positive and 154 test negative. You know that 6 people have covid-19 in the sample of 10,000. So 84.6% of 6 or about 5 people in the sample will have covid-19 and correctly test positive.

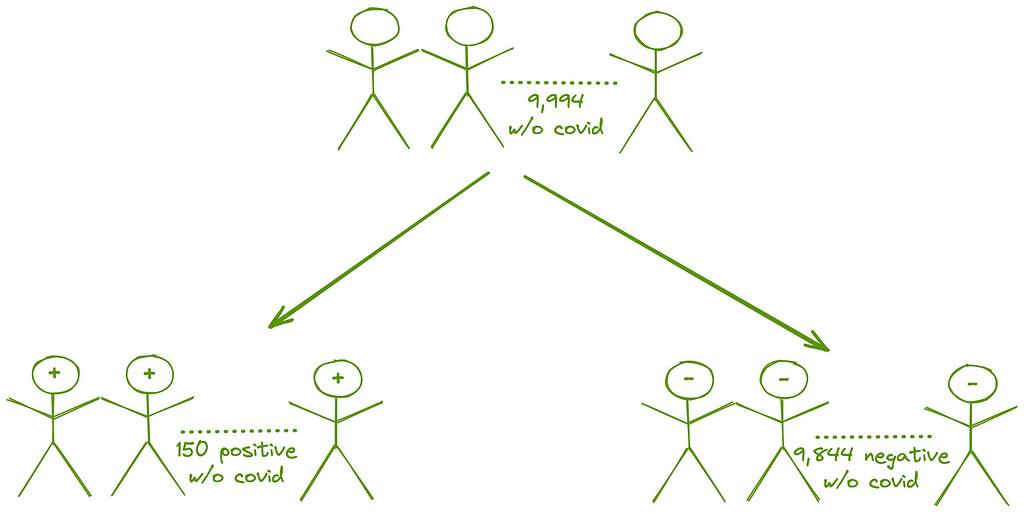

2. What is the likelihood of the evidence, if the hypothesis is false? In this case, how likely is it that you test positive despite not actually having covid-19? This is the false positive rate. According to the data there is a 1.5% false positive rate. You know that 9,994 people do not have covid-19 in the sample of 10,000. So 1.5% of 9,994 or about 150 people will be covid-free and yet test positive.

Now that you have the true positive and false positive rates, what is the posterior likelihood of the truth of the hypothesis that you have covid-19? It is the number of people in the sample who have covid-19 as well as test positive divided by the number of people in the sample who test positive regardless of whether they actually have covid-19. Expressed as a percentage the result is 5 / (5 + 150) * 100 or ~4%. The evidence updates the likelihood of you having covid-19 from the prior 0.064% to the posterior 4%.

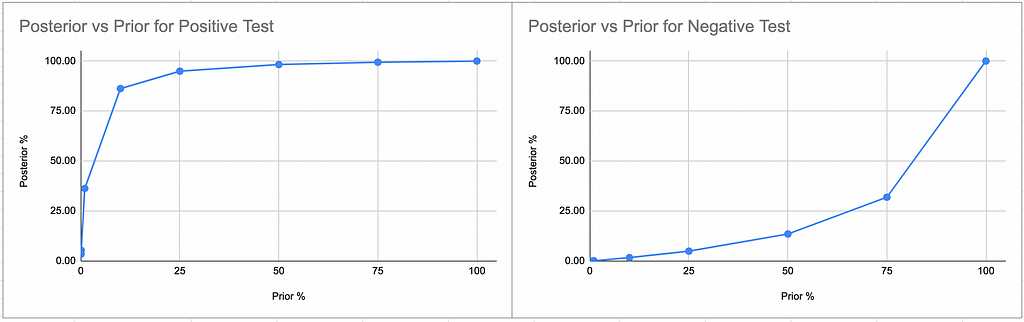

Only a 4% chance of actually having covid-19 despite having tested positive in an at-home rapid test? Yep. The low prevalence of the disease where I live (which depresses the prior likelihood), combined with the non-zero, albeit small, false positive rate, leads to a very low-confidence positive test. So don’t be overly worried with such a positive result. But don’t ignore it either! Use it as an indicator that you should confirm the result with a high-specificity test (like the molecular PCR test).

What about the alternative case in which you tested negative? If you have covid-19, the test has a 15.4% chance of showing negative. This is the likelihood of the evidence being true if the hypothesis is true (the true positive rate for the evidence). Alternatively, if you don’t have covid-19, the test has a 98.5% chance of showing negative (the false positive rate for the evidence). With the same prior likelihood as before of 0.064%, the posterior likelihood of having covid-19 turns out to be 0.010% or 1 in 10,000. You should feel pretty safe. No need for any further testing unless you are symptomatic or suspect recent exposure.

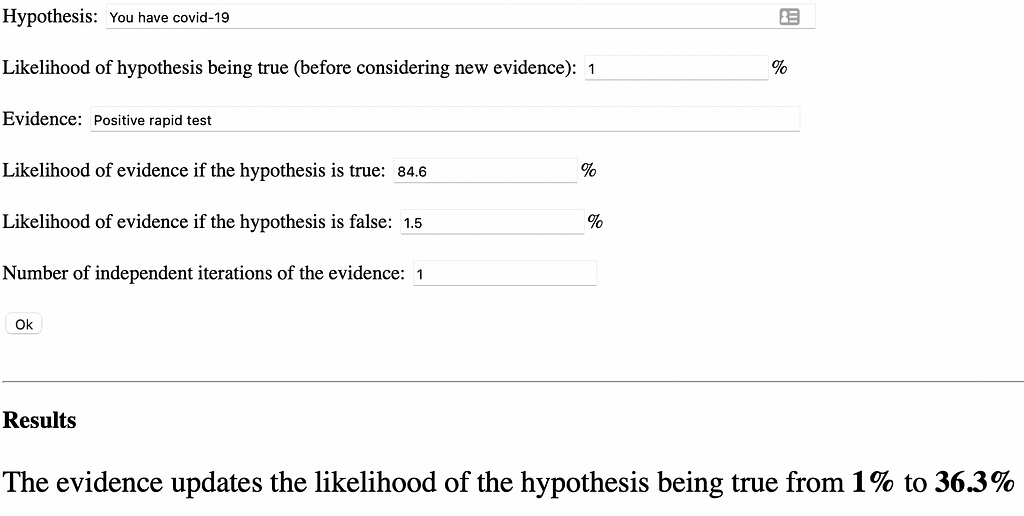

What if the prior likelihood of having covid-19 is higher? Not all infected people get tested, so the reported case rate is certainly an underestimate. Besides, you could live in a high-case-rate area, or have symptoms, or have been recently exposed to someone with covid-19. Then a positive test result is indeed worrisome and warrants action. Even with a modest increase of the prior likelihood to 1%, the posterior likelihood of having covid-19 after a positive test increases to a more significant 36%.

The key take away is that a screening test result does not mean that the result is certainly true. A recent ad on TV for an at-home cancer-screening test confidently claimed to “find 92% of colon cancers overall”. But when you correctly factor in the evidence of a positive test, fewer than 1 in 4 of the people who test positive actually have cancer. Before you take any drastic actions based on test results, evaluate the results correctly and proportion your belief to the evidence¹.

How Can You Evaluate The Evidence More Easily?

Don’t worry, you don’t have to do any tedious calculations every time you have to evaluate some piece of evidence for a hypothesis. As long as you’re clear-headed about what the hypothesis is, what the evidence is, and what the true-positive and false-positive rates for the evidence are, you can simply enter the values in a tool and get the updated posterior likelihood. If you have difficulty finding such a tool, feel free to use my rough prototype at https://vishesh-khemani.github.io/bayesian/bayesian.html.

What Kinds Of Scenarios Can This Be Used For?

Is Your Friend Winning By Cheating?

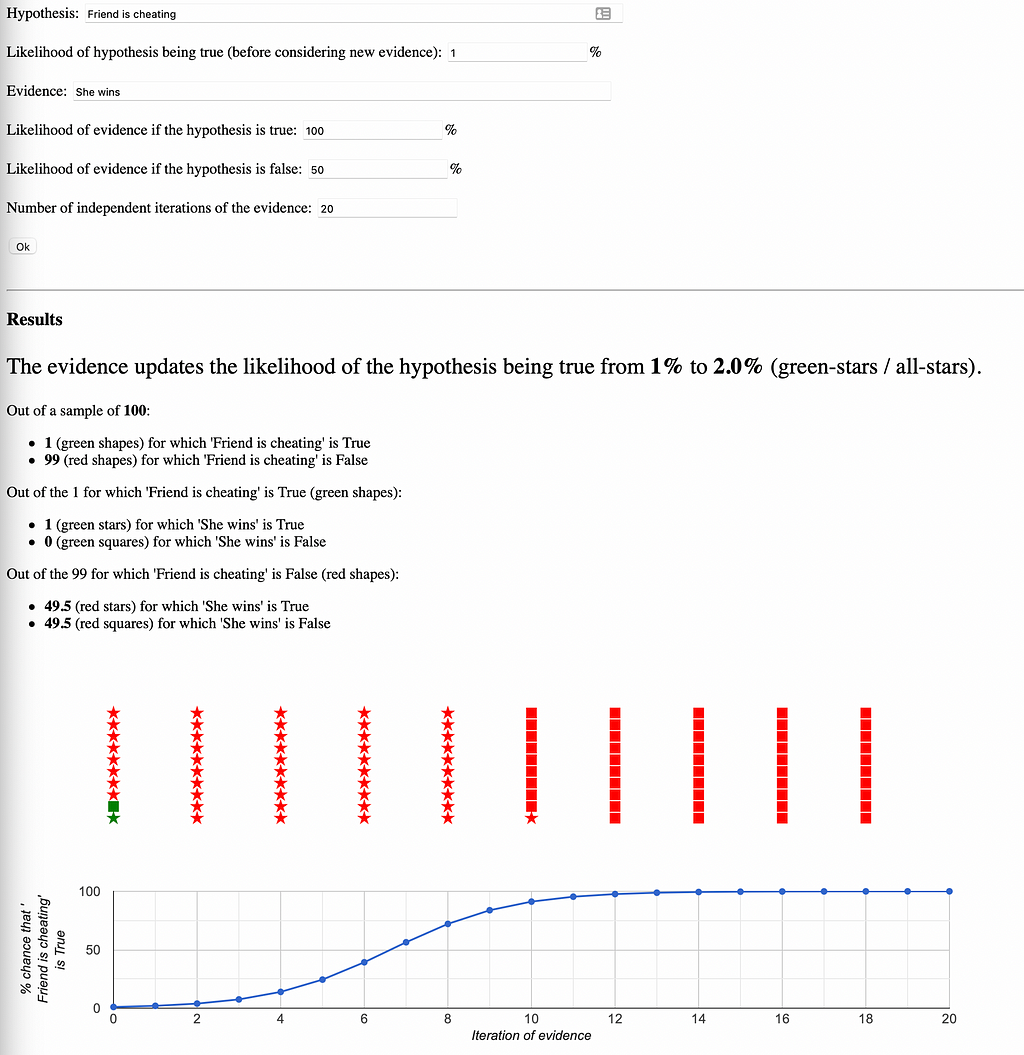

Imagine you play a luck-based game with your friend in which either of you is equally likely to win a round. For example, the game is getting a higher roll than your opponent on a dice. Or winning a coin toss. Then you find that your friend keeps winning. After how many losses would you be willing to jeopardize your friendship and accuse her of cheating?

If you’ve known your friend for a long time and never found a reason to doubt her honesty, your estimate of the prior likelihood of her cheating will be low, say 1%. The chance of her winning if she’s cheating is 100%. The chance of her winning if she’s not cheating is 50%. Enter these numbers in the tool and you find that after her 7th win it’s more likely than not that she’s cheating and after her 10th win she’s most likely cheating. I’d be willing to accuse her with those odds.

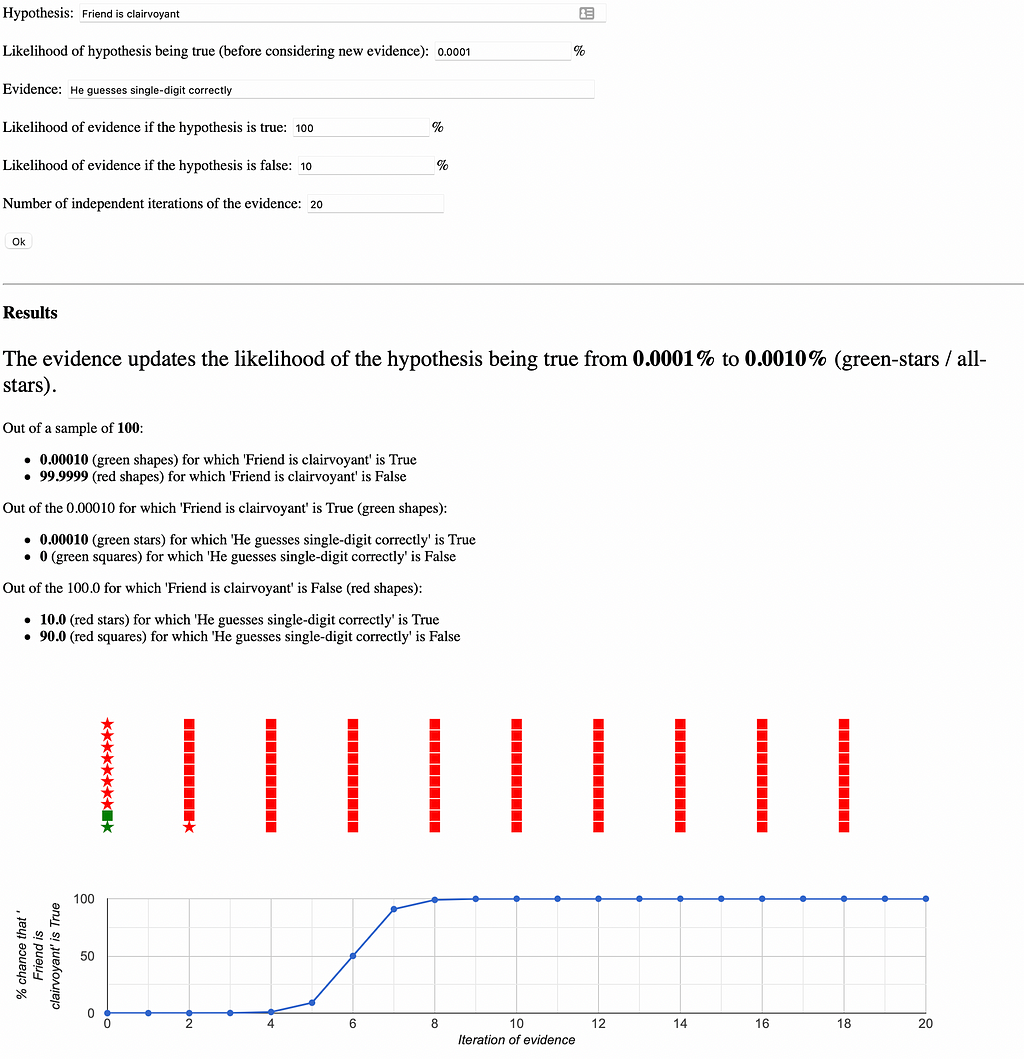

Is Your Friend Clairvoyant?

A friend claims to be able to read your mind and guess a single-digit number that you think of. You don’t believe in such nonsense and ascribe a low prior likelihood of 0.0001% (or 1 in a million) that your friend’s claim is true. Then, to your surprise, he guesses your number. And again. After how many correct guesses will you change your mind and believe in your friend’s clairvoyance?

After 6 correct guesses, the odds are in favor of clairvoyance! I personally don’t think this can happen, but hey, remember to keep an open mind and proportion your beliefs to the evidence.

Is The Defendant Guilty?

You are on the jury for the trial of a defendant charged with a robbery. The robbery occurred in a small town. DNA at the crime scene matched the DNA of the accused. However, the defendant had an alibi. Also, an eyewitness at the robbery did not identify the defendant as the robber in a police lineup. Do you find the defendant guilty or not guilty?

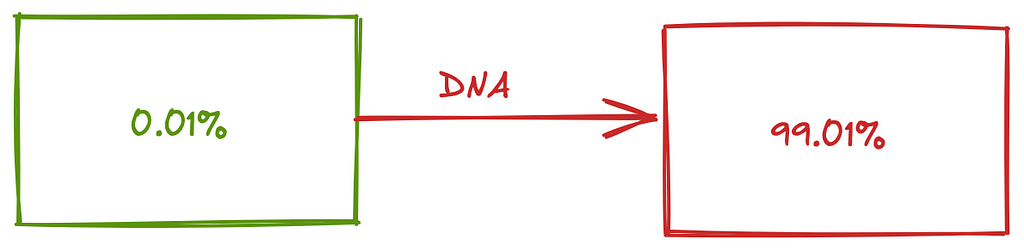

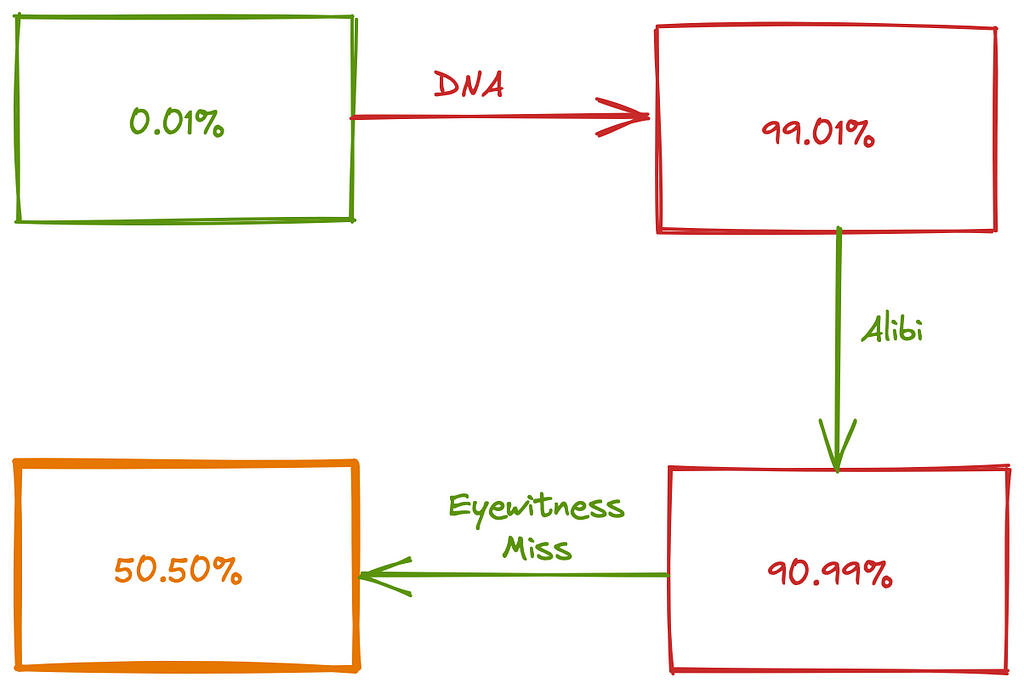

You start with estimating the prior likelihood of guilt. The robbery appeared to be a random act and could have been perpetrated by anyone in the town. The town’s adult population is 10,000. So you estimate that the defendant has a 1 in 10,000 chance (0.01%) of being guilty (prior to considering any evidence).

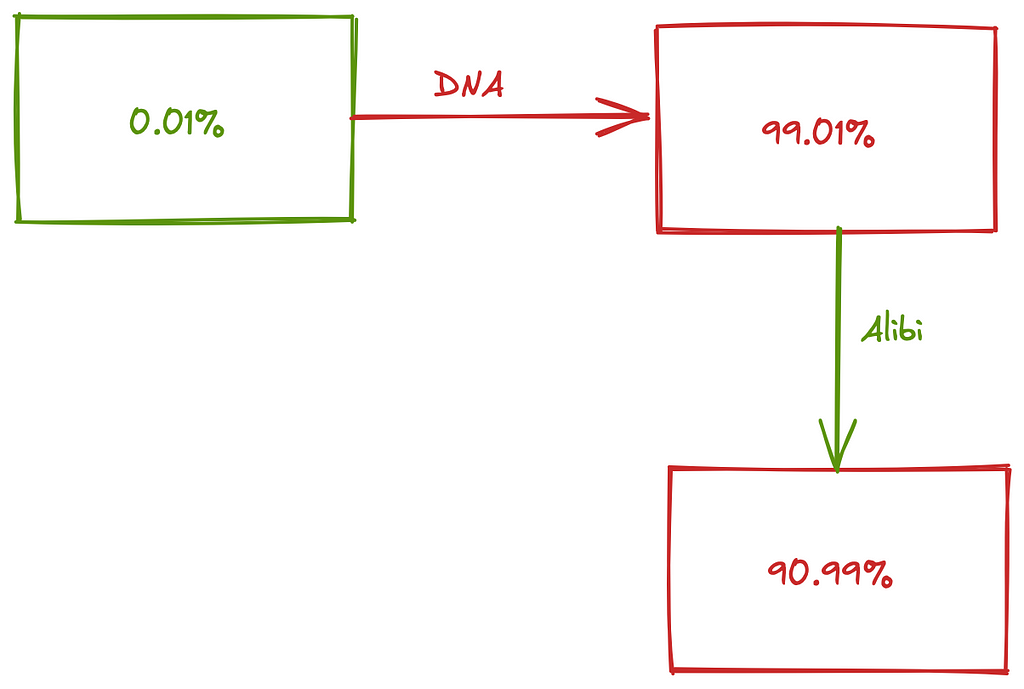

You then consider the first piece of evidence: the DNA match. If the defendant is guilty, the DNA is certain to match. An expert witness testified at the trial that the likelihood of any random person (including the defendant) matching the DNA at the crime scene is 1 in a million. So, if the defendant is not guilty, the likelihood of a DNA match is 0.0001%. This evidence updates the likelihood of guilt from 0.01% to 99.01%. The DNA match is extremely incriminating.

You next examine the alibi evidence. The defendant’s wife claimed that he was grocery shopping at the time of the robbery. A checkout clerk at the store corroborated seeing the defendant at the store. If the defendant is guilty, his wife is probably lying and the checkout clerk is either mistaken or lying. You estimate that the likelihood of both the wife and the store employee providing incorrect information is 10%. On the other hand, if the defendant is not guilty, then the alibi is likely true, say with 99% certainty. With this evidence, the likelihood of guilt goes from 99.01% to 90.99%.

The final piece of evidence is that the eyewitness did not identify the defendant in a police lineup. If guilty, this would be unlikely, but possible with a likelihood of say 10%. If not guilty, this would seem to be the expected outcome, so the likelihood of not being identified is high, say 99%. Now the chance of guilt goes from 90.99% to 50.50%.

A 51% chance of guilt is way below the bar of guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. You find the defendant not guilty.

How would you have come to a verdict without the above principled approach to evaluating the evidence? You would do what almost all jurors do: use your gut. And you know what? Most people’s gut tells them that a DNA match (with only a 1 in a million chance of a random person matching) points beyond a reasonable doubt at guilt. The other exculpating evidence would be drowned out, perhaps unfairly attributed to human error or deceit.

You are now armed with the knowledge and tools to update your confidence in your beliefs by evaluating relevant evidence. It’s ok to have preconceived notions, as long as you keep an open mind to honestly evaluate any new data (especially if it’s contrary to your belief). Go forth and believe rationally.

References

- An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding — David Hume

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayesian_inference

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antigen-tests-guidelines.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R_v_Adams

Believe Rationally was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

from Towards Data Science - Medium https://ift.tt/31n89bL

via RiYo Analytics

No comments