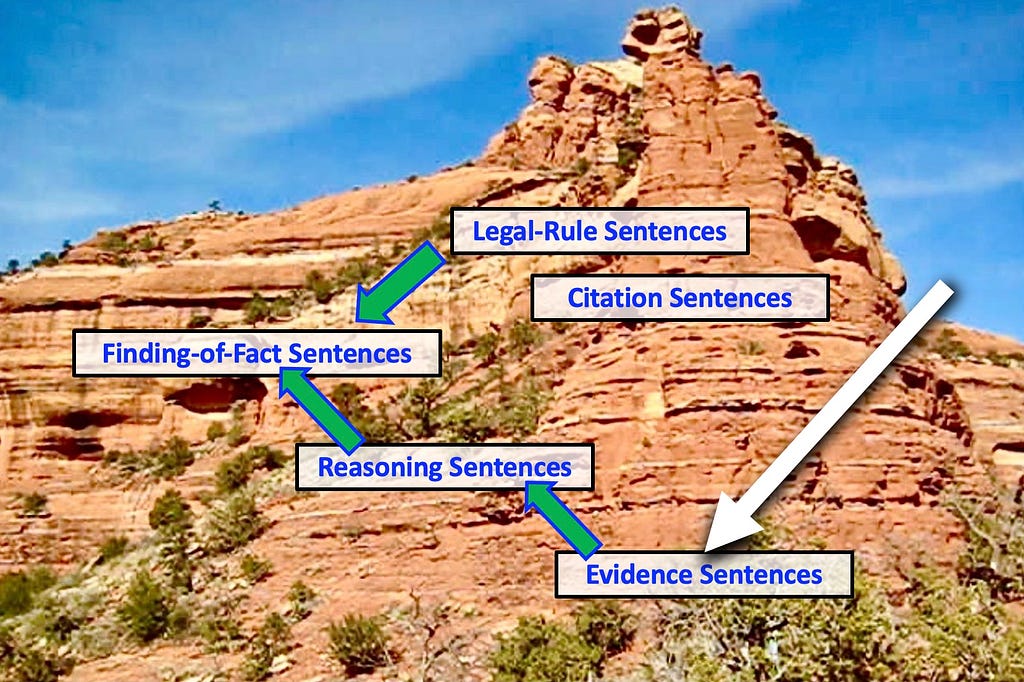

https://ift.tt/3Ih6e8g Identify the evidence to mine the legal reasoning Image by Vern R. Walker, CC BY 4.0 . In any legal case, it is ...

Identify the evidence to mine the legal reasoning

In any legal case, it is the evidence that makes that case unique. That same evidence also determines which other cases could be considered “similar” cases — and the rule of law requires that similar cases should be decided similarly. So, the evidence in a case is specific to it, but the types of evidence tend to be generic to cases classified as similar.

The lawyers for the parties, faced with the legal issues to be proved, must decide what evidence to produce. They look to previous similar cases and the governing legal rules for guidance. To assist lawyers and judges, and for other reasons, data scientists face the problem of extracting from published case decisions the evidence that was considered relevant and important.

In this article, I discuss what legal evidence is and its role in legal reasoning and argument. I also discuss the linguistic features that make it possible for machine-learning (ML) algorithms to automatically extract the important evidence from legal decision documents.

The Roles and Types of Legal Evidence

In a typical legal case, the initiating party has the burden of producing evidence to support a decision in that party’s favor. Opposing parties try to undermine the credibility or trustworthiness of that evidence, and they might produce more evidence that is contrary or inconsistent. Opponents might also produce evidence to support any affirmative legal defenses that raise new legal issues. As a result, evidence might be offered from all sides of a legal case.

The evidence can consist of testimony, documents, and physical evidence. Testimonial evidence is provided by a witness giving testimony under oath about what she or he has seen or heard, or by an expert witness giving an opinion based upon the witness’s expertise. Documentary evidence can come from various sources, such as medical or business records. Physical evidence, such as a physical object, can also be introduced as evidence.

Once the tribunal rules which offered evidence is relevant and admissible to the case, the lawyers present arguments about what the admitted evidence proves with regard to the legal issues at stake. The tribunal’s trier of fact (e.g., jury, judge, or administrative decision maker) must assess the probative value of that evidence and reach findings of fact. For example, the trier of fact might discount the credibility of a witness’s testimony, or it might consider a particular document’s contents to be trustworthy. The trier of fact also evaluates the probative value of all the evidence taken together, and it reaches conclusions of fact concerning the legal issues.

Sentences Stating the Evidence

A decision written by a tribunal is a good place to start in mining the evidence. It typically recites the important evidence involved, and it also explains (except where the trier of fact is a jury) the reasoning from that evidence to the findings of fact. Lawyers and others studying the decision want to determine which evidence was used to reach which finding or conclusion. The decision can generate a suggestive list of what evidence to produce in a similar case, depending on the legal issue. Also, data scientists might generate statistics about various types of legal cases, based on the evidence.

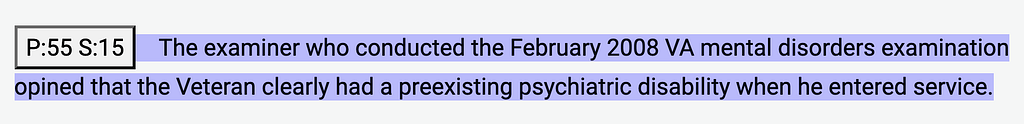

In a legal decision document, an evidence sentence is a sentence that primarily states the content of a witness’s testimony or of a document introduced as evidence, or that neutrally describes the evidence. An example of an evidence sentence is the following (as displayed in a web application developed by Apprentice Systems, Inc., with the blue background color that signals an evidence sentence, and a rectangular icon identifying the sentence as occurring in paragraph 55 of the document, sentence 15):

This sentence reports the opinion of a medical examiner. (My examples are from decisions of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA), which decides claims by U.S. military veterans for benefits due to service-related disabilities.)

Ideally, an evidence sentence merely reports the evidence without evaluating it. This distinction between reporting and evaluating allows us to separate the evidence itself from the assessment of its probative value by a particular trier of fact. The distinction is sometimes difficult to apply to whole sentences, however, because judges might combine a report of the evidence and an evaluation of that evidence into a single sentence. Nevertheless, judges have an incentive to write decisions that first lay out the important evidence in a neutral way. As a result, we often can identify sentences that primarily state the important evidence without evaluating it.

Linguistic Features of Evidence Sentences

To identify the evidence sentences in a decision, lawyers use various linguistic cues or features. Often the sentence contains a cue (a word or phrase) that warrants the reader to attribute some proposition to an evidence source. Examples of evidence-attribution cues are: “the witness testified that,” “in the opinion of the expert witness,” and “in his report the examining physician noted.” The likelihood of such a sentence being an evidence sentence increases if what is being attributed is punctuated as a quotation.

Other linguistic features include whether the sentence:

· Immediately precedes, or contains within it, a citation to a source in the evidentiary record (e.g., a hearing transcript);

· Contains only definite subjects, referring to specific persons, places or things (in contrast to legal rules about indefinite subjects);

· Contains no universal quantifiers (e.g., “all” or “any”); or

· Contains no deontic words or phrases expressing obligation, permission or prohibition (e.g., “must” or “requires”).

Other features include occurrence within a paragraph that is dedicated to a recitation of the evidence. Therefore, a wide variety of linguistic signals can indicate that a sentence is stating evidence. (For more details and numerous examples, you can check the protocol for annotating evidence sentences, which I created and published when I was Director of Hofstra Law’s Law, Logic & Technology Research Laboratory (LLT Lab).)

Machine-Learning Results

As we might expect given the linguistic features of evidence sentences, ML algorithms can learn to identify those sentences that primarily state the evidence. We trained a Logistic Regression model on the LLT Lab’s dataset of 50 BVA decisions, which contained 5,797 manually labeled sentences after preprocessing, 2,419 of which were evidence sentences. The model classified evidence sentences with precision = 0.87 and recall = 0.94. We later trained a neural network (NN) model on the same BVA dataset, and we tested it on 1,846 manually labeled sentences. The model precision for evidence sentences was 0.88, and the recall was 0.95.

A recent study we conducted suggests that ML algorithms may be able to accurately identify evidence sentences after training on even fewer labeled data. Using the LLT Lab’s dataset of 50 BVA decisions, we analyzed the impact of increasing the size of the training set, from as little as one case decision up to 40 decisions (with 10 of the total 50 decisions set aside as a test set). Using the weighted average F1-score as the performance metric, we found that the training for evidence sentences achieved F1-scores well above 0.8 after as few as 5 decisions, and the scores reached a plateau soon thereafter. We hypothesized that the “semantic homogeneity” of evidence sentences to each other as a class may help explain this outcome.

There is also reason to think that, once evidence sentences are identified, ML algorithms can extract from them important information about the evidence in the case. The linguistic cues discussed above suggest that attribution theory can help us extract lists of evidence sources, which we can then classify into types. We might also extract a list of propositions for which there is at least some evidence in the legal record.

Practical Error Analysis

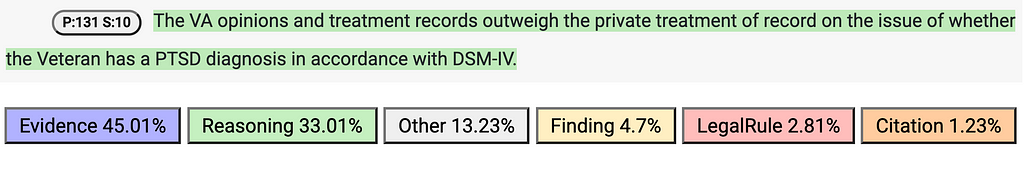

In the first ML experiment I mentioned above, the NN model predicted 740 sentences to be evidence sentences. Of these, 89 were misclassifications, and about two-thirds of these errors (60 sentences) consisted of misclassifying reasoning sentences as evidence sentences. This is understandable when you consider that many reasoning sentences are about evaluating the credibility or trustworthiness of items of evidence. For example, the trained NN model misclassified the following sentence as an evidence sentence, when it is actually a reasoning sentence (as signaled by the green background color):

This sentence refers to the evidence, but it does so in order to explain the tribunal’s reasoning that the probative value of the evidence from the Veterans’ Administration (VA) outweighed that of the private treatment evidence. The prediction scores for the possible sentence roles (shown below the sentence text in this screenshot from the Legal Apprentice web application) show that the NN model predicted this to be an evidence sentence (score = 45.01%), although reasoning sentence also received a relatively high score (33.01%).

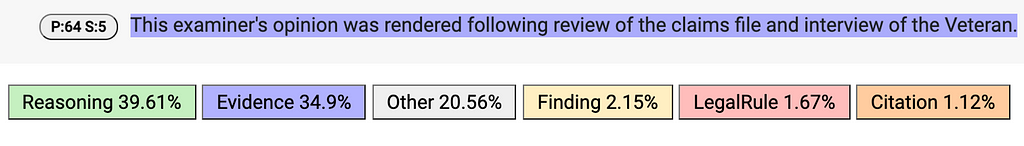

The NN model also occasionally misclassified evidence sentences as reasoning sentences. Of 686 manually labeled evidence sentences, the model misclassified 24 as reasoning sentences. For example, the trained model predicted the following evidence sentence (manually labeled, highlighted in blue) to be a reasoning sentence:

While this sentence merely recites the basis for an examiner’s expert opinion, the NN model classified the sentence as stating the reasoning of the tribunal itself. The prediction scores of the model show that the confusion was a close call: reasoning sentence (39.61%) vs. evidence sentence (34.9%).

As a practical matter, for some use cases, a precision of 0.88 and a recall of 0.95 can be adequate. Such a model could extract and present numerous acceptable examples of evidence from similar cases, with very little noise. This is particularly true if the main confusion, when it occurs, is between evidence sentences and reasoning sentences about the evidence. A user of such an application might still consider such query results informative for guiding arguments in a later case.

On the other hand, such error rates might not be acceptable if the goal is to gather statistics about the types of evidence relied upon in decided cases, or to measure the extent of bias in fact finding. Sampling theory would then require the calculation of confidence intervals around the frequency estimates, and such measurement uncertainty might prove unacceptable.

Summary

In sum, there are many reasons to identify the evidence sentences in a written legal decision, especially if the objective is mining the legal reasoning found in similar cases. Evidence sentences help identify past decisions that might be similar to a new case. Such sentences also identify what kinds of evidence played an important role in those similar cases, and they can help guide the production of evidence in a future case. There are both theoretical and experimental bases for concluding that ML algorithms can learn (A) to automatically identify those sentences that primarily state the evidence, and (B) to automatically extract from those sentences some important information about that evidence. Evidence sentences are therefore an important key to classifying legal cases.

The Evidence Is Critical for Classifying Legal Cases was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

from Towards Data Science - Medium https://ift.tt/33SKUH2

via RiYo Analytics

No comments